Русская версия статьи - Russian version

Barış Manço is famous in Turkey primarily for his music. He stood at the foundation of Anatolian rock, that is, the synthesis of Eastern and Western music. At the beginning of this work, he took well-known folk songs (“türkü”) and translated them into the Western minor mode, retaining, nevertheless, the main musical meaning of the melody. Soon he began to write his own things in the Anatolian "synthetic" style. Sometimes they were characterized by unusual tones. I wrote about this in more detail in an article about Anatolian rock in Russian. There I came to the conclusion that the synthesis of such different modes as the eastern maqam and the western major minor led Manço and other Anatolians to expand their musical consciousness. But in general, in music, Manço is primarily a melodist.

Now I want to dwell in more detail on the lyrics of Manço's songs. Manço himself said that he was more a poet than a composer, that he wrote songs for the sake of sense. Music is a way to make the sense more intelligible. Here he downplayed the importance of music, but he wanted to draw attention to his lyrics in this way.

All Anatolian authors wrote lyrics focusing on the tradition of ashiks. Ashiks are oriental bards. Sometimes they are compared with medieval troubadours, but this is not entirely correct. Firstly, the ashik movement and style has existed almost to the present day. Secondly, the poetry of ashiks is purely oriental. Oriental poetry is for the most part sublime, metaphorical and figurative, often religious. European troubadours did not become famous for their great poetry, and ashiks wrote brilliant poems.

There is a tradition in the poetry of ashiks that comes from the Sufis. All of them constantly mention as their teachers Rumi (in Turkey they call him Mevlana) and Pir Sultan Ablal. The latter was an Alevi, not a Sufi, but in relation to orthodox Islam, these things are similar. Both doctrines emphasize human morality and kindness, and not the implementation of accepted laws. It is quite natural that in the 60s, the years of the appearance of rock and the search for free thought, such non-canonical religiosity was in demand.

Manço is a typical non-canonical believer. From Islam, he takes, in fact, only moral and mystical themes, but not dogmatics. His most profound and programmatic thing about religion is Dört kapı (Four doors). Even in his love songs, there are constant references to the separation of the soul from the body, the Day of Judgment, angels and paradise. There is also a song reminiscent of Christmas - Bugün bayram (Today is a holiday). In his youth, he studied in Europe, he understood Christianity well and did not consider it hostile to Islam. In Bugün bayram there is a striking line: "During the holidays, the angels are sad." It reminds me very much in spirit of the Sufis, who have always paid attention to mental states and appreciated sadness. It bring you closer to God (probably, sincere joy too), and not prayer with words without meaning.

And here I want to say the main thing about the work of Manço. If you take all his things together, it is obvious that with his songs he created a world. It must be assumed that he first invented this world for himself. As far as I understand, for all his external sociability and goodwill, on a deeper level he was deeply immersed in himself. As is typical for creators, he was almost entirely egocentric, not in a psychological sense, but in an existential one: His disposition was directed only at his own experiences and the images and fantasies that were born from them. Here, for example, is an early piece of Kol düğmeleri (Cufflinks). So you clearly see a child or teenager sorting through buttons and inventing sad stories about their parting.

True, there are exceptions: the song Sarı çizmeli Mehmet ağa (Mr. Mehmet in yellow boots) is dedicated to a real person. Manço even tracked down his grave in Cyprus and landscaped it. So he could sometimes leave his world and act in reality. But what do we learn from this song? Nothing, it is a sermon. It is, in fact, the first Manço's explicit sermon, followed by a dozen more (Kazma, Ahmet Bey'in Ceketi, Ce sera le temps, Dıral Dede'nin Düdüğü, Eğri eğri doğru doğru, Halil İbrahim Sofrası, Hemşerim Memleket Nire, Olmaya Devlet Cihanda, Yol). Moreover, Manço obviously worked hard and willingly on the manner of preaching. His sermons are unpretentious, without pressure, with remarkable self-irony. Not to mention that they are set to pleasant, again completely unpretentious music. His videos for songs are just as warm and soft, for example - Ahmet beyin ceketi (Mr. Ahmet's jacket).

So the first thing to be said about Manço's world: it is religious, with a keen desire for kindness. This is probably not the same thing, but it seems to me that Sufis were close to him in both. It is interesting, by the way, that most of the songs with sermons in his music have a clear Turkish touch. And existential reflections - almost everything in music is purely European. In a musical sense, his world remained somewhat ambivalent.

Some of his sermons are not so much religious, they are rather about the fact that life passes, that it would be nice to get into a better world where there is no death (Abbas yolcu, Traveler Abbas). But sometimes he writes that the road does not end even after death (Yol, Road). The image of the road is generally very common in Turkish poetry, but it is interesting about the afterlife road. I would like to know where it leads.

He has excellent self-irony in the second video for Bugün bayram, where he smiles at his love for rings on his fingers. Self-irony in general speaks of the reflexive elaboration of the inner world.

However, in his last things everything is different, softness disappears, sometimes replaced by pure despair. In the last period of his life, Manço generally changed a lot, became much harder and more serious. Albums began to be released less frequently, and he mainly engaged in television programs in which he talked about different countries and cultures. He left his own, previously so close to him, world, and passed into reality. He returned to his world in order to express his saddest states. It's very clear in songs like Benden öte benden ziyade from the last album. Here he is not up to irony, the feeling of imminent death prevails over everything.

But back to a brighter period. What else is felt first of all in the world of Manço - this world is very warm. Whatever he writes about, he has warm music, warm words, he sings with warm intonations. Here, for example, is the wonderful thing Arkadaşım Eşek (My friend the donkey). Love for animals in it is a symbol of love for the divine world.

Of course, as a great connoisseur of the nonsens, I love the nonsense in his poetry. I know nothing about absurdist poetry in Turkey. The most typical example of Manço is the song Acih da bağa vir, both the title and the text of which can at least somehow be interpreted only by the Turks. He has very original lines in many other songs, for example, Adem Oğlu Kızgın Fırın Havva Kızı Mercimek (Adam's son is a red-hot furnace, and Eve's daughter is lentils). In his world, he loved surprises.

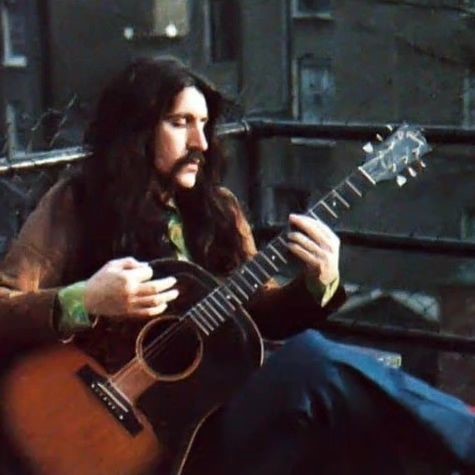

Naturally, Manço also has a lot of love songs. Any most refined world cannot be imagined without it. His love is exclusively for women (which would not be obvious from his appearance in his youth). I would like to focus on the female images from his songs.

One of the songs of genius in its simplicity and light mood is Halhal (Bracelet). He himself once told about it: I wanted to write about a free girl who lives as she wants and loves whom she wants. Manço's women are always independent, live their own lives. The lyrical hero basically waits for what they will tell him (and often weeps, however, not here).

He developed this subject to its logical conclusion in the incendiary song Anahtar (Key), in which the girl is completely inaccessible, she is engaged only in science, and the author admires her, but his mother advises him not to waste his energy in vain, "the girl is too smart." The song is very cheerful, so Manço does not regret at all about the feminist orientation.

And the lyrical hero himself - is this Manço or not? More likely no than yes. Or rather, this is who he was in his world. He was definitely different in real life, but that didn't matter to him. It can be said that together with the world he built his image, what he could be.

One of the masterpieces of the early third period is the song Hatırlasana (Remember). This is a thing of sadness and despair, in which the whole Manço's world is reflected very clearly. In terms of content, it most likely has nothing to do with the real life of the author. He just needed to say something important to him. This is a song about tears, about the existential truth of powerlessness. Powerlessness is an existential (in the words of Heidegger), along with horror, anguish, determination and all that we know from philosophy. There is no need to fight with powerlessness, it must capture to the end, it reformats a person, in the future it gives wisdom. You don't even have to look strong. There is no need to avoid tears and hide them. In general, Manço wrote a lot about tears, starting with the early Ali yazar Veli bozar (Ali writes, Veli spoils), but it was not enough for him, and Hatırlasana was written specifically for this.

This softness and weakness does not in the least prevent joy in relation to the world, on the contrary, it facilitates its acceptance. On the same album on which Hatırlasana was released - the album Darısı Başınıza 1989 - there is also a light Domates biber partlıcan (Tomatoes, peppers, eggplants), and an important, seemingly cheerful children's, but in fact a serious pacifist piece Günaydın çocuklar (Good morning, children). Both of them, and many others that follow, do not bear any rejection of the world. Manço, even during the period of depression, did not write that he wanted to die, he accepted life. Although he has many references to death, and also calm and with acceptance: my God will call me, I will go to another world, and it’s good. There are angels there

Four of his later songs form his testament. These are Ömrümün Sonbaharında (At the Autumn of My Life), Hatırlasana, Beyhude Geçti Yıllar (Years gone in vain) and Benden öte benden ziyade (More than me, higher that me). From the sad statement that life passes, and, perhaps, passes in vain, he sees one way out: in faith in God.

That, in fact, is the most basic thing that I wanted to say about the senses of the world of Barış Manço. As mentioned above, the latest album from this series is a little out of the way. It is quite heavy, it is not even clear whether Manço then had the energy to build this world of his own. Beyhude geçti yıllar (Years gone in vain) at first sight is a love song, but in fact it is the result of his disappointment. Even in purely love things from this album, there are such lines as “Beat me as you like, just don’t leave” (Al beni - Take me), which was not typical of him before. He found meaning in sadness, but it was not masochism. It is impossible to say what he would eventually come to, at the age of 56 he died. From the last album Benden öte benden ziyade is like the result of his testament: four Muslim books and God, who always remains higher, but always with you, always ready to call to him.

It's good that such authors exist